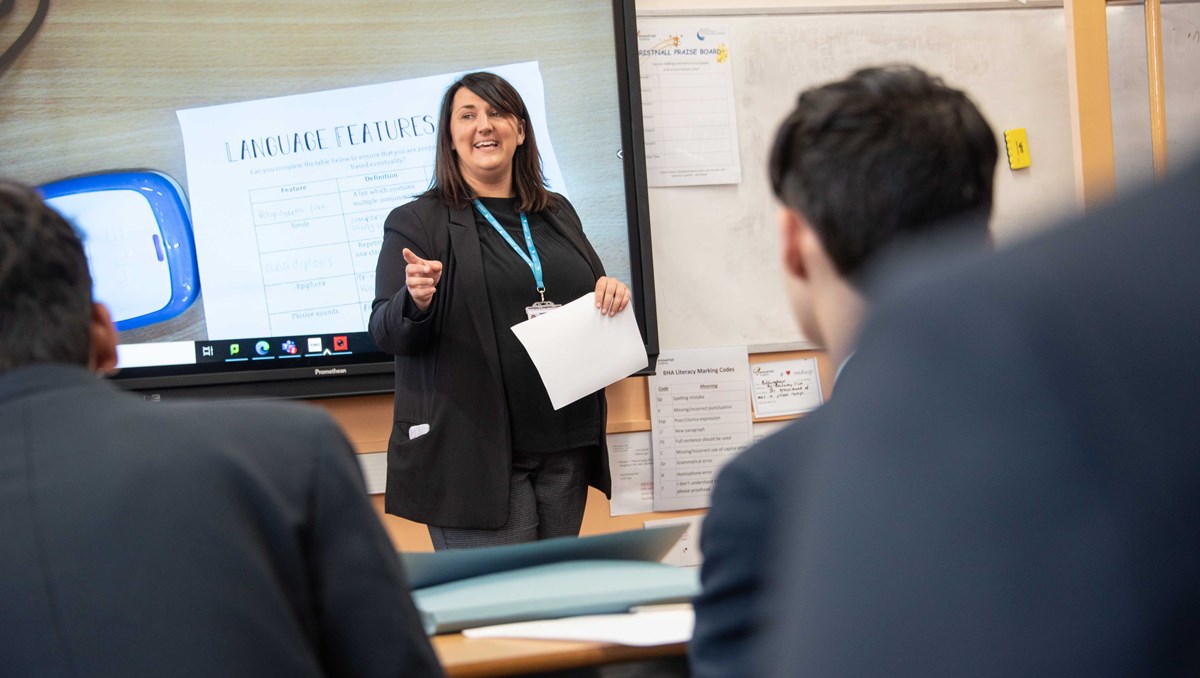

Building a culture of wellbeing in schools

It is the culture of a school which determines how well the mental health and wellbeing of teachers, staff and leaders is supported. Andrew Cowley looks at way this supportive culture can be built.

Articles / 6 mins read

For the past five years, Education Support have been asking teachers from across the UK about their experiences of mental health and wellbeing as part of their Teacher Wellbeing Index. This year’s report will be the most important yet, providing insights into the working lives of teachers and education staff during the pandemic, while contextualising that experience within five years of data.

Key findings:

- 77% of staff in schools are experiencing symptoms of poor mental health due to their work.

- 72% of staff are reporting feelings of stress. This rises to 84% for senior leaders.

- 46% of staff, rising to 54% for senior leaders, go into work despite feeling unwell.

- 54% of staff have considered leaving the profession in the past two years because of the pressures on their mental health.

- 42% of staff feel that an organisation’s culture is having a negative impact on their wellbeing.

Arguably it is the culture of a school which determines how well the staff and the leadership can be supported in their mental health and wellbeing.

77%

of education staff are experiencing symptoms of poor mental health due to their work

Are wellbeing cultures built or grown?

Anything that is built, your school building for example, is solid and tangible, reasonably permanent and largely unchanging aside from the occasional aesthetic improvement. Something that is grown requires different care; it needs to be nurtured, developed, given the right conditions, in which to thrive and survive. Any gardener will know that runner beans need support to reach their height and full potential. The same too applies to any culture, which can thrive only in fertile environments, without the challenges which stop it growing in the first place or hamper it after germination. We can have a culture of wellbeing in school, just as we might have a culture of learning, a culture of artistic appreciation or, less positively, a culture of bullying.

Cultures also need to sit alongside relationships. Where relationships are sound, people feel supported and can be challenged to improve without feeling threatened. Where relationships are toxic, workplaces become divided, unnecessarily stressful and unhappy places to be. Given current concerns about staff retention, with 54% of staff considering their future in teaching, positive working relationships and a mutually supportive culture are essential to our profession.

“Myths” about wellbeing

At its core, wellbeing is a simple concept meaning the absence of illness or the act of being well. Although, as a school leader wellbeing isn’t always easy to get right (especially if the school culture doesn’t support it). By avoiding these ‘myths’ about wellbeing, and by acting more strategically, it is possible to kick start a positive culture.

Myths to avoid:

- Wellbeing is a soft option, sorted with a few nice toiletries and cakes in the staffroom

This isn’t wellbeing, but nice things to do. The teacher sat in their room over lunch desperately ensuring all the marking policy requirements are met and may never reach the cake intended for them, the teaching assistant on break duty may return to the staffroom to find no more than a few crumbs on a plate. - Meditation and mindfulness will solve everything

Provided in some schools as a form of self-care, this ignores the fact that self-care is a personal choice and such practises can make some people feel uncomfortable. - A wellbeing day represents a culture of wellbeing

Again it doesn’t. This is not to suggest that schools shouldn’t hold such a day, but the messages from such an occasion need to ripple through the school year. Team building activities in early September matter little when staff face busy weeks later in the Autumn term, juggling assessment deadlines, pressures around Christmas productions and the impact of the cold and influenza season.

Getting the culture wrong

Wellbeing goes wrong where attitudes are negative and cynical, where staff don’t feel trusted or experience undue pressure and stress. A certain amount of stress can be expected in any workplace, but stress as in the short term can lead to low mood, fatigue and , irritability. In the long term it can have devastating impacts upon health, leading to burn-out and insomnia, high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. We cannot manage colds or broken bones, but we can provide leadership in managing the reduction of stress related illness.

Working hours remain an issue, 35% of all staff and 66% of senior leaders work in excess of 51 hours a week, despite not being contracted to do so. Given the statistics around presenteeism and the link with how the organisational culture is perceived, we need to question if there is a fear of consequence for absence, related to accountability for results and progress or if the fear relates to a lack of trust. Less than half of staff questioned felt fully trusted by their line manager, and 91% of those who felt distrusted believed this negatively impacted their wellbeing, and 63% of this group would always turn up for work despite feeling unwell.

Some of this impact on school cultures may go back to initial teacher training, where 74% felt they had insufficient preparation for looking after their own wellbeing. As these teachers move into leadership and line management roles, if they don’t have the tools to look after their own wellbeing, will they have the facility to support those they manage? 57% of staff would not be confident in disclosing unmanageable stress to their employer, 29% feel there is a stigma about discussing their mental health problems, yet only 34% report that wellbeing is subject to a regular survey. There may be school leaders who feel uncomfortable about conducting such a survey, fearing it may simply be used to air criticisms, but it is a crucial piece of evidence and conducted regularly can form part of a positive and reflective culture.

Fixing the culture

There are no easy solutions, no quick fixes, but being open to talking, and that talking not being about work and pupil progress, would be a good start.

Work-life balance is a constant issue for teachers, but having that balance is crucial to making our colleagues the people they want to be; happy and satisfied with what they have achieved, rather than burnt-out and miserable.

Prioritising wellbeing, eliminating the stigma around mental health, challenging negativity, looking after our leaders and supporting staff. These central to our education recovery plans. Let’s do what we can to keep them there.

Andrew Cowley is a former primary Deputy Headteacher who now coaches for the School Mental Health Award and Designated Wellbeing Leaders qualification. He is also the author of “The Wellbeing Toolkit” and “The Wellbeing Curriculum” both published by Bloomsbury Education.

Our service provides emotional and practical support that helps you and your colleagues thrive at work.

Fully funded professional supervision for school and FE college leaders in England and Wales.