Talking to colleagues about their mental health and wellbeing

We’re all becoming more aware of mental health issues at work. But how do you start a conversation with a colleague you’re worried about?

Articles / 5 mins read

"My plate is full at the moment, but thank you for thinking of me"

Having open and honest conversations about our mental health and wellbeing are an important part of creating a culture where people feel valued, cared for and supported. No one is born with the skills to have good conversations, it’s something we all have to learn and practice. You don’t need to have all the answers. Good conversations about mental health are about asking open questions, showing you care, listening and showing empathy, and withholding personal judgements.

If you’re wondering where to start, read on:

Create the right environment

Before starting a conversation with someone about their mental health, make sure you’re in a safe and confidential space. No pupils or colleagues should be able to overhear you. You should be free from distractions and be able to commit the time needed for the conversation. The time should also be right for the person you’re checking in on.

Asking open questions

Open questions tend to start with words and phrases like: what, how, tell me more about, when and who. They are based on curiosity and creating a space for people to explore or process their feelings.

Some examples include.

- How would you describe your wellbeing today? Give it a score of 1-10?

- How would you describe your stress levels at the moment?

- How would you describe your resilience?

- Tell me more about what you’re finding challenging about that?

- What suggestions do you have to improve your wellbeing? What can you do, what can I do, what can the school or college do?

- If you had to change one thing to improve your wellbeing what would it be?

- I have noticed that you are leaving work most nights at 6.30pm. Tell me more about what is going on at the moment?

Active Listening is another important tool. The same is to make the speaker feel seen, heard and understood, which in turn makes them feel safe and often relieved. To active listen you can:

- Summarise or paraphrase so the person feels understood e.g. ‘it sounds like you are saying’ or ‘so what I’m hearing is’

- Reflect back their emotional experience e.g. ‘it sounds like you have had a really tough time with no one to help out’ or ‘there has been a lot going on and you are feeling overwhelmed.’

- Show you are being attentive by giving open body language and eye contact

- If you ask how they are, do not take I’m fine as an answer say. Be curious, ask something like – ‘can you tell me a bit more’ or ‘you’re very good at coping with challenges, I wonder if there’s anything particularly challenging now’

Show you care

Asking the questions and listening without judgement is a really caring act. In our busy lives, how often are we able to talk freely, and be really heard?

Don’t be tempted to rush to a solution or action, just be there and listen with curiosity before you get to that stage together.

Another way of demonstrating that you care, is to be reliable. If you say you will do something or address a concern then follow up with that promise. Not doing so will erode trust and may lead to the person thinking you don’t care.

When people feel cared about, they feel safe and this is likely to minimise the flight or fight or stress hormones that can make them feel anxious and overwhelmed.

Hold back your judgement

Hold back on your point of view and your personal judgements. No matter how well-meaning your advice may be, a conversation about someone’s mental health should be about giving them a safe space to express themselves.

Practice Carl Roger talks about the need to hold someone in unconditional positive regard. One thing this means is observing your own judgements but not letting the person you’re talking to feel them. For example, in a conversation about mental health, you may privately not understand why a situation has created such a strong reaction in the person you are talking to. But to voice this would undermine any feelings of trust and support you have built. There will likely be things going on that you don’t understand.

Carl Rogers advises that we observe our judgements, and work out what we know factually and what you do not.

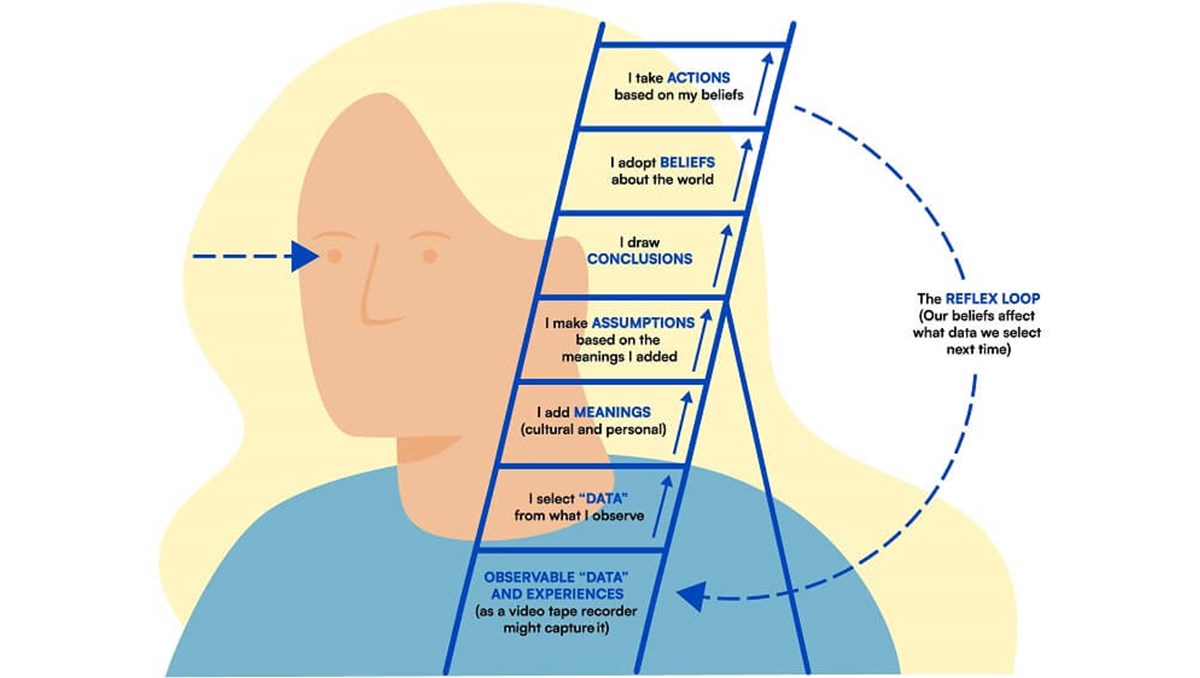

Another thing to consider is the Ladder of Inference:

Example:

The Observable Data is I see someone crying. I may jump to the top of my ladder to think they are not coping. I may think they are stressed and overwhelmed.

They could be crying with joy or pride. A pupil could have achieved something brilliant due to that person’s support.

Before jumping to a conclusion, acknowledge your jump in thinking (up the ladder!). When talking to the person start with the observable data (you are crying) and then ask open questions to find out more e.g. I can see you are crying, talk to me about how you are feeling.

Finally

If you are concerned that someone is in crisis (e.g. if they are having a panic attack, cannot get out of bed, are seeing or hearing things that you cannot) they may need professional help.

- Encourage them to call our helpline for emotional support: 08000 562 561

- Offer to accompany them to the doctor

- If they are at risk to themselves or someone else, take them to A&E

Don’t wait for a crisis to call.

We’ll offer you immediate, emotional support.

08000 562 561

Sign up to our newsletter for the latest mental heath and wellbeing resources, news and events straight to your inbox.