Looking after yourself & each other in education settings

These tips will help you to look after yourself and build support with colleagues, growing resilience across your setting, promote and support staff wellbeing, build understanding of stress, recovery and trauma and reduce risk of burnout.

Guides / 22 mins read

Created in partnership with MindEd

Created in partnership with MindEd

Knowledge and understanding of ourselves and each other, our relationships, are at the heart of good support. Some people call this being psychologically aware.

Being psychologically aware supports positive social connectedness, which in turn builds wellbeing and grows resilience. It is important to recognise how this complements the duty on employers of education staff to look after their health, safety and welfare.

This set of top tips from our international panel of health and education experts, adapted for the education workforce are to help you:

- Look after yourself and build support with colleagues, growing resilience across your setting

- Promote and support staff wellbeing

- Build understanding of stress, recovery and trauma

- Reduce risk of burnout

There are two main sections: ‘things to do’ and ‘things to know’. Use this resource as works for you. The headline tips give quick access advice, the drop-downs beneath each tip provide more detail.

Things to do

Look after yourself, that is essential, so you can then look after others

- Keep healthy

Keep your body and mind in good shape with healthy living habits including exercise, choosing healthy food, allowing time to eat, keeping hydrated, and getting regular sleep. - Stay safe

In the thick of challenging or stressful events when you need to keep going, make a mental note of the need to recover when it’s safe and sensible to do so.After a traumatic event take extra care when driving or doing anything potentially dangerous; put off difficult and demanding tasks temporarily. - Belong

Maintain positive relationships with those around you. - Feel good

Preserve leisure time, even short times out can make a big difference. - Give back

After any event, give time for things to settle and for people to regain some calm, then allow yourself time to reflect without blame; “How did I look after myself and my colleagues?”; “How did we do as a team?” Don’t get stuck in this phase though, keep it time limited.

With colleagues, encourage social connectedness with those around you. Every interaction matters

- Stay healthy

Share positive social communications within your team, such as healthy recipe swaps or encouragement for a sporting goal, but don’t insist others join in. - Stay safe

Be a good bystander. Challenge gossip or teasing comments that could hurt the feelings of others. - Belong

A small word or a little help, can make a big difference. Stick small stars in places where your eye will catch sight of them. Resolve to find a positive to mention about someone else every time you spot a star. - Feel good

Relationships are key; at work, at home and in our communities, they always matter. Take time to invest in your relationships with others -be curious and open to learning from each other. Consider learning more about relational practice or conflict resolution. - Give back

Help to make collective spaces such as the staff room, good places for social connection. Remember that different staff members have different needs relating to social connectedness. Who never comes into the staff room? Do they have other ways of having social connection? Are they isolated, or does lunch on their own meet their own needs well?

Within our community, reflect on the impact of distress on families and how this may added

- Keep healthy

We are social beings and are attuned to detect the emotional states of others, children in particular. This can amplify the positive and the negative emotions for each of us. Negative emotions are unlikely to be helpful to those we wish to help and so if we struggle with these, we each may need to seek help to manage this. - Stay safe

Remember, the same is likely taking place for many children too. As social beings we are all impacted by those around us. This of course includes children who are often very affected by and mindful of others’ distress. Listen and consider their ideas of how best to support them and their peers. - Belong

The notion of emotional contagion means that the mood held by one, or a few, can quickly spread to others. We want to encourage our school community to be respectful of the grief of others in ways that are supportive to the child or family affected. There is no ‘one size fits all’ strategy. Hear what the child and family want: support may be through assembly, shared information, reflection, discussion, symbols, sorrow, perhaps fundraising.

Offering ways for children and staff to share their feelings individually or in class or whole school settings will help to reduce the type of emotional contagion that could be more detrimental to healing.

If a child is going through distress, consider, reflect, and make a conscious effort to consider how this is impacting on you, as this will affect how you respond to the child. Take a moment to think and decide how you will respond and manage this. - Feel good

At times of distress for a child or young person they may appreciate our empathy and value us being upset for them, but it is important not to inadvertently make them feel somehow responsible for our sadness. Remind or train yourself and colleagues of the framework you have for supporting yourself and others e.g. 5Rs are a mnemonic that we introduce in our tips on stress and trauma in education. - Give back

Be aware of the toll the distress of others can take on ourselves. Check in regularly with colleagues (e.g. supervision) who are working closely with a child or young person affected by a trauma, such as a death of a parent. If you are the person close to the child, then make sure you find frequent emotional time away from the situation, e.g. listen to music in your break time.

Be sensitive to the feelings of others

- Be aware of your own motives in helping others

- Offer support but don’t force it. Not everyone will welcome your support – don’t take it personally

- You don’t need to know everything, only what the other person volunteers or chooses to tell you

- Be aware some may find an event triggers previous feelings – just quietly being there may be helpful

One antidote to stress is kindness

- Acts of kindness ripple across teams

- Knowingly being kind can be as effective as a spontaneous gesture

- Make a point of being kind, set out to be kind, be open to receiving kindness from others

- If someone says a positive thing about someone else in conversation, share that good message with the person who was mentioned

Nurture hope - it helps us cope

Help yourself and colleagues to:

- Find ways to laugh together when reflecting on the day. Smiling and laughing are a tonic

- Hold in mind a time when you felt hurt or fear, and remember how these feelings passed. Tell yourselves that these feelings will pass too

- Support each other, as this gives hope. Hopefulness is very important for psychosocial resilience and wellbeing. It makes us feel we can make a positive difference and achieve our own goals

- Acknowledge what we should be grateful for, but don’t make this a competition!

- Learn new skills - growing together as a team promotes optimism

It’s ok not to be ok

- It is important to give the physical and emotional space for this to be true, whether for yourself or for those you are supporting

- Know who on your team has the skills to handle team members’ distress

- Know when to hand over to another who may be better placed to help

- Prioritise a distressed team member’s need to be safe over your curiosity to know what happened

Professional supervision can support an educational role and personal wellbeing

- Taking time to talk about your professional practice is important. Someone taking time to help shape and guide your conversation can make you feel more valued and validated

- If you provide or receive professional supervision, bear in mind that meetings don’t need to be frequent, but do need to be regular

- There are a variety of ways of providing time and space for professional conversations. This may include mentoring, coaching, peer supervision, or a more formalised structure of professional supervision

- A good performance management cycle should include regular opportunities for professional reflection with a line manager or colleague

- You may need time with a colleague, or senior leader, to reflect upon some of the more challenging aspects of your role too, such as a child with complex needs and disabilities, or a parent with mental health needs that can impact on you at the end of the day

- There are organisations that can provide professional supervision or training for staff to develop a structure of professional supervision in your own school (see resources section)

Prioritise your time for the supervision

- You may well have many other things to do but committing to the meeting builds trust and adds value

- Professional supervision has many benefits: psychologically speaking it helps participants to learn from experiences and so to be empowered. When that happens, our wellbeing is supported, and resilience is being built

- Keep the meeting focused on your agreed goals, whilst leaving enough space for feelings and reflections too

- Find a space for the supervision where you won’t be disturbed

- Valuing professional development helps everyone

Listening skills: things to remember

Listen very carefully, using body language that encourages and supports your colleague:

- Listen first, speak second

- Reflect back what you think you heard, e.g. ‘You mentioned you feel anxious before you leave the house in the morning’

- Check you have it right, e.g. ‘Did you mean to say that…’

- Ask open questions if you are unsure, e.g. ‘How did that make you feel?’

- Summarise in as few words as possible

- Don’t judge

- Repeat with open questions for example “What else is on your mind at the moment?”

- Respond appropriately – beware of leaping into premature action, be open to working out a collaborative plan

- Solving others' problems can be the easy bit – supporting someone to find solutions to their own problems is the skilful act

- Develop the ability to empathically tune in without emotional contagion – bad feelings can be ‘catching’. It is important for the listener to keep some neutrality, particularly if the issue relates to individuals within the workplace

- Relevant skills can be developed via free learning from Education Support and supported by mindfulness-based approaches. Further learning is available on mindfulness here

Be part of a team that welcomes training and information

- Get trauma-informed (see links in the resources section)

- Develop attachment awareness (see links in the resources section)

- Understand mental health first aid principles (see links in the resources section)

- Develop listening and (operational) debriefing skills. N.B. These skills are different from psychological debriefing immediately following traumatic events, which is not recommended because it has been found to increase risk for subsequent Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Develop professional supervision skills (training is available)

- Ensure a range of staff are trained to support debriefing following an incident (see below). There is strength in sharing these skills across the staff team

- Be familiar with key policies, including critical incident management plans, behaviour policy, restrictive physical intervention policy and health and safety policy, and understand how they relate to staff wellbeing

- Promote the important messages in your team and challenge where these policies could be improved, including through staff governors

Be honest and prepare together - risk assessment in action

- Be honest with each other about the risks or challenges you may face in a school or college day and plan together to reduce that risk

- Consider structuring thinking, plans and actions using tools such as the “circles of control, influence and concern” to understand roles within wider complex systems. See here for more info, and diagram for a summary:

- There may be personal psychological risks. Help others to know what is in place to reduce that risk and the range of support available

- Share the reasons you do the job. Help to reinforce a strong sense of professional identity with the role

- Reinforce the value of the role as individuals and team members

- Check key policies, prioritise staff safety and wellbeing and feed back to senior managers if there are gaps

Encourage responsibility, not blame

- Model ways to be reflective after an incident. Remember you are all on the same team/ be clear that everyone’s long term goals are likely to be shared – this helps shift away from blame and towards making sense of why the outcome was not ‘what we all wanted’, and therefore ‘how we might all do things differently next time’

- Look for signs of others blaming themselves and support them to reflect – ‘next time I could…’

- Don’t say sorry when you are really wanting others to say sorry

- Discourage others from talking negatively about another person’s role in an incident

- Play a role in making sure a child or young person is not blamed for an incident either. Model language that doesn’t retaliate but helps to restore. Sanction may be appropriate, but humiliation isn’t. Focus on the behaviour not the person

Make sure you know the system for debriefing staff following an incident

- Following an incident of aggressive behaviour from a child or young person, for instance, or a difficult confrontation with a parent, it is important to talk with someone about what happened in a non-judgemental way. This can include any feelings at the time of the incident and at the point of reflection.

- Use a framework of questions (see here for an example ) to help debrief, to support reflection rather than recrimination (blaming of self or the child). Debriefing can enable the individual to reflect, recover and consider strategies for professional development or prevention. The process can also help to review whole school approaches and safer practice. Examples of questions are:

- What did you expect to happen?

- What actually occurred?

- Why was there a difference?

- What might you do differently next time?

- What else can be learned?

- Learning and understanding behaviours is a huge topic in itself, but aim to see every behaviour as a communication: the ABCC can help:

- What were the Antecedents to the behaviour?

- What Behaviour followed the antecedents?

- What were the Consequences (for all concerned) that followed?

- What do you think was the intended communication of the behaviour?

- Focus on what could be different if the same events were to happen again.

- Debriefing (not to be confused with post traumatic event psychological debriefing) is an important skill set for at least one member of school to have. Other staff should know who is able to support them in this way. Facilitating effective debriefing within a school or college setting is a skill that may require training.

- These are supportive ways to relieve the build-up of stress during daily school life by sharing and learning from each other

NB. Information may need to be obtained and shared for legal and risk management purposes, for example, if staff used a restrictive physical intervention with a child who was at risk of harming themselves or others, or if a child was transported to hospital from a school lesson.

Things to know

Knowing who to speak with

- Be shrewd in identifying support, both in and out of work, and who you can share your feelings with safely

- Balance this with not overloading the same person all the time. Try to make space to hear their feelings too

Thinking patterns

- Growing our minds and learning, including post-trauma growth, is a protective factor for our mental health

- Post traumatic growth is when, following a trauma, we discover and learn new things that build our psychosocial resilience, and we feel psychologically stronger

- Our minds need time and care to rebalance, rest and recover

- Good relationships help to moderate negative thoughts and support more positive thinking patterns: keeping balance in perspective and attributions of events, breaking down problems to manageable chunks, supporting a sense of I can/agency/hope/support and much more

Psychosocial resilience

- Psychosocial describes the psychological, emotional, social and physical responses of a person or group of people to an external pressure, such as an incident or emergency

- Resilience describes the internal ‘toolkit’ a person or indeed a team has to manage or overcome difficulties caused by external pressure, including workload stress

- Psychosocial resilience is dynamic; it can increase, for example through gaining new skills, learning, and adding tools to your kit. It can also decrease through loss of confidence or feeling under-skilled or overwhelmed

- Remember some days we are more resilient than others; mind and body fluctuate day-to-day regardless of external events

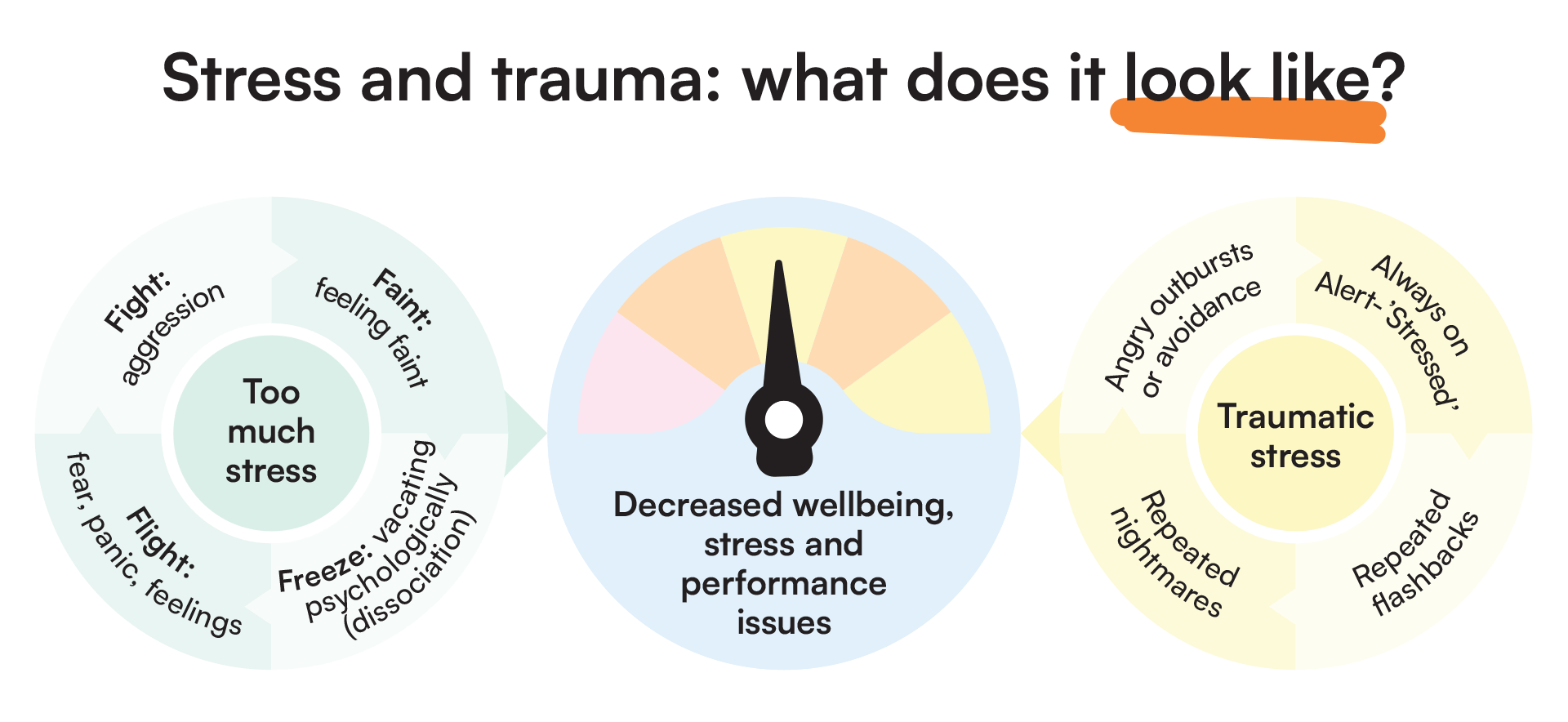

How to explain some of the language of stress and recovery.

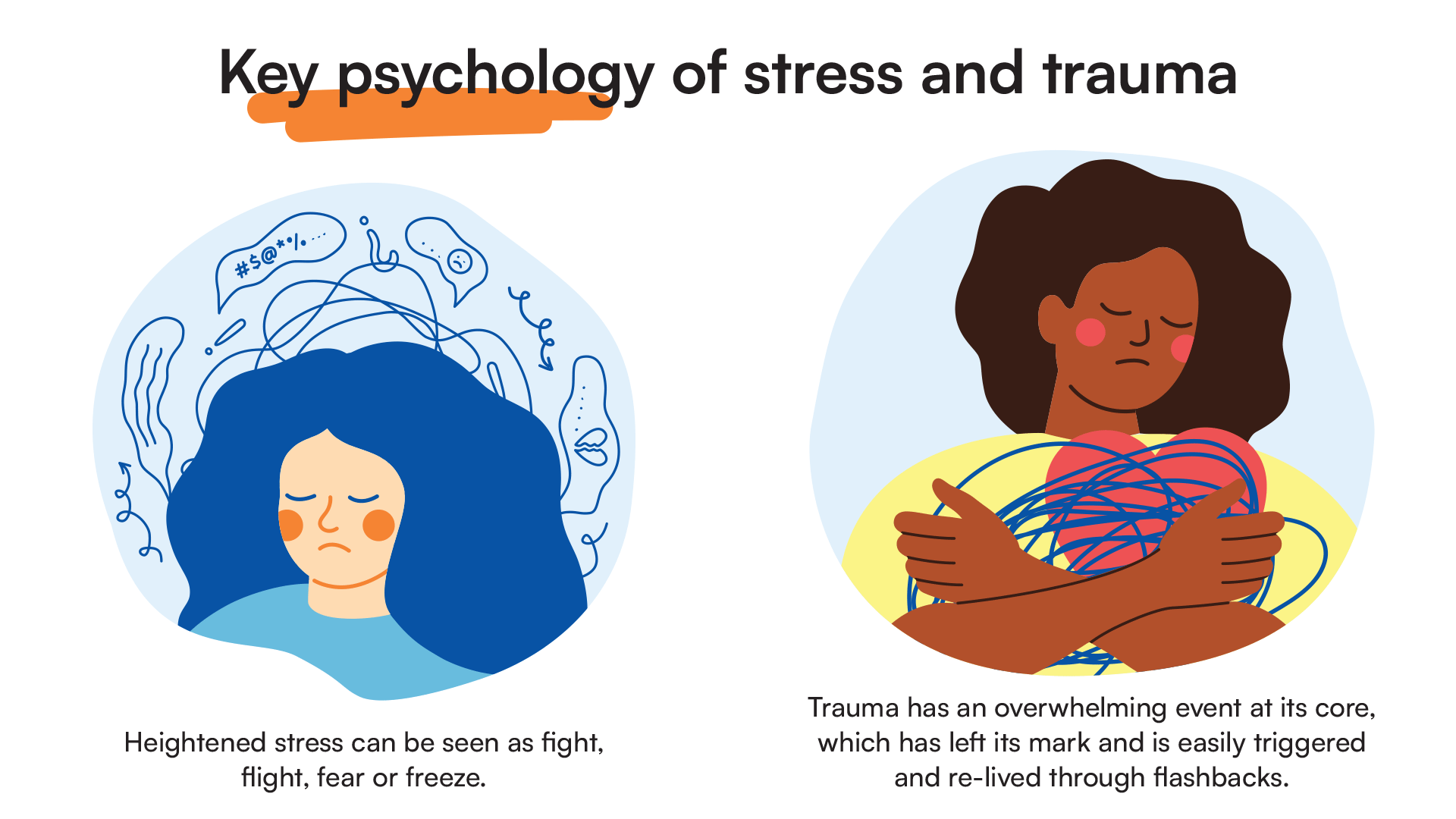

Stress - this occurs when the external demands made on us exceed the resources we have available to manage them

- When we feel stressed there are likely to be good reasons for this

- Our bodies cope with stress by producing hormones, adrenaline and cortisol. Think of it like surfing; you can anticipate the wave and use it to power you to overcome the difficulty, or you can come off your board and the wave will crash around you and take you in directions you may not have wanted

- Adrenalin can create a ‘fight or flight’ response, which can leave you feeling less in control of your emotions and actions, adding to further stress

- Good colleagues help. Good colleagues who are part of collaborative and united teams, within psychologically smart organisations, help even more

- Be aware: pressure once experienced as stimulating and exciting, may become unpleasant and exhausting if repeated time and again – creating feelings of burn-out in a work context

- A potentially stressful situation can enable people to react positively to a short-term emergency, such as a broken leg in the playground

- Chronic and extended crises, such as a pandemic, can be stressful, for example if a school or college is reacting to constantly changing guidance, rules and systems

- Considered responses or systems that are well communicated ease the risk of stress

- Emergencies accelerate the impact of existing vulnerability/stress

- Stress can also occur in anticipation of events, especially when demands are greater than our resources for managing

- Stress is a physical and emotional response to external factors. Anxiety can occur at the same time but tends to be an ongoing and sometimes excessive worry. The physical features of stress and anxiety can appear similar, such as sleeplessness, headaches, irritability, anger, and digestive problems

- Stress is not a defined mental health condition, but it can be the precursor to many illnesses

Repetitive stress - ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back’

- Education staff must manage a huge amount within the role and environment that requires effective coping skills; workload, external accountability, meeting special additional needs including special educational needs, challenging behaviour and sometimes confrontational relationships

- Events coped with successfully, sometimes for years, may still have had a cumulative effect. This is hard to notice. It can gradually reduce psychosocial resilience and bring you or your colleagues close to a tipping point

- It may be that other external pressures, such as personal relationship or health concerns, combine with work related stress

- In this state, any additional stress may suddenly prove too much, such that our coping ability collapses

- Stress will rarely just affect an individual. Education staff should consider contacting their trade union/Education Support or other external support services for help and advice when factors such as workload and accountability become unmanageable

- Employers have a legal duty to undertake stress risk assessments and take appropriate action. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Stress Management Standards -What are the Management Standards? - Stress - are a helpful tool in this respect

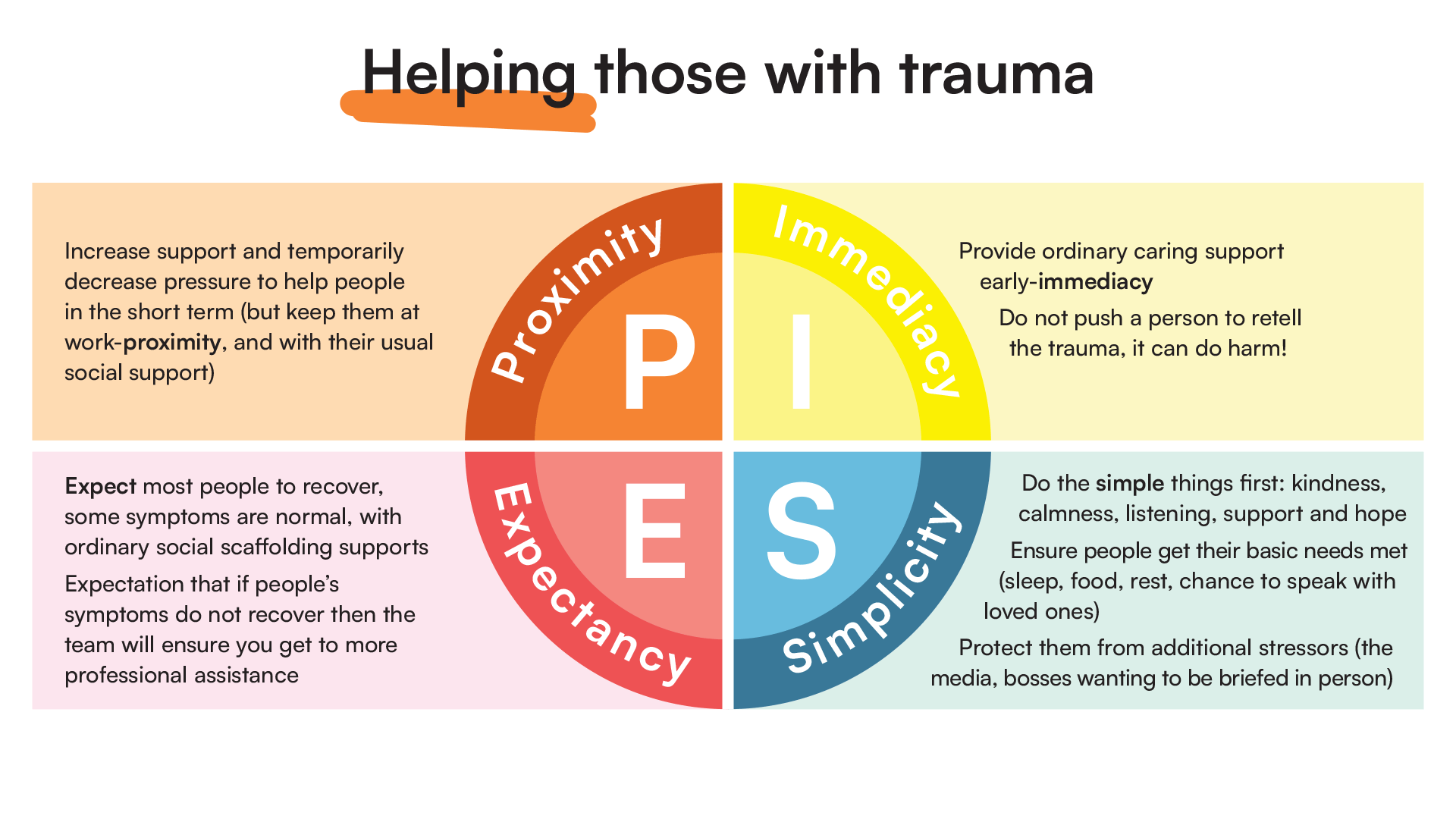

Traumatic stress -this refers to events that are often sudden and shocking

- These events have been described as like puncturing a ‘mental skin’. An example of a critical incident that may trigger traumatic stress in a school might be a coach crash, or a child knocked over on the way to school. It could be about a member of staff dying. This type of incident can impact on people who witness it, as well as those who have to manage the ripples, such as children being upset

- We need time and sensible support to recover after such events; this should be anticipated in education teams

- Most of the time, the majority of people do recover if things are supportive (as described in these tips) and stable (not being retraumatised, not being over worked/distressed, relationships stable) over the following weeks: look out for colleagues not recovering after 4 weeks

- We discuss stress and trauma further in our linked tipsheet see here: it is important to remember some children are experience multiple and repeated traumas in their home lives. For more learning about Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) see the Minded detailed elearning

Learn what stress is and what clinical depression and anxiety look like

Stress, anxiety and depression (see our tips on Stress and Trauma for what to look for) are usually the biggest causes of sickness in education settings – in the 2021 Teacher Wellbeing Index, 72% of education professionals reported that they felt stressed, 10% up on the previous year.

- Mental health difficulties do not always result in staff absence. Many staff report that they don’t feel they can take time off for mental health reasons and this can result in being there in body but not in spirit (presenteeism)

-

- Monitor your own and others’ stress

- Work out what works as ‘stress buster’ for you, e.g mindfulness, yoga, exercise, music, knitting

- Use strategies to help you think about the aspects that you feel are causing your stress and then contain them safely, for example, imagine a chest or bucket in which you put the stressful factors, and put the vessel somewhere safe (in your imagination) until you have time or emotional space to reflect

- Have a bank of stress busters that you know work for you, ready and available; don’t assume you’ll just find them when you need to in a hurry

- Be ready to review and change your approach if one stress buster no longer works, reflect on this, and change it. Make time to consider and experiment with your solutions and how you respond

- Know what help is available both from your organisation and externally

- There should be clear pathways and resources available in all organisations

- Confront the fear of the unknown by finding out what your school policies say in relation to mental health and wellbeing (not yet a statutory policy), staff absence and Health and Safety

- Seek to be part of a culture of openness and honesty around the legitimacy of staff absence due to mental health – this all adds to reducing the stigma, we should be able to speak of it like we might about physical illness

- Speak to a staff governor or a member of the leadership team if you feel your school policies could be positively amended to better reflect mental health and wellbeing in the workplace

- Allay anxieties about help-seeking

- Consider seeking support from external agencies such Education Support, health services/GP, and or your trade union. It is vital to tackle the root causes of stress for education staff. This may for example be related to workload and accountability pressures or lack of professional discretion. It may be non-work related. In either event, achieving positive change in these areas will provide a solid basis for staff to be able to focus on looking after themselves and others

Resources

Within education settings

- Wellbeing or mental health policy should offer local sources of support. See NEU Mental Health Charter NEU Mental Health Charter | NEU. https://neu.org.uk/advice/neu-mental-health-charter

- Occupational Health – in most local authorities you can self-refer, or work with your senior management to arrange a referral. Within academies you may have access to occupational health as an external service.

- Work-related stress and how to manage it: https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/risk-assessment.htm

- 2021 Teacher Wellbeing Index: Education Support

Education focussed external resources

Trade Unions and Professional Bodies

NHS external resources

Reflective conversations and professional supervision

- Education Support e learning on reflective conversations in education settings

- Talking Heads Supervision Ltd – Supervision Curious

- Charlie Waller Trust – advice on supervision

-

Barnardos - Supervision in Education – Healthier Schools for All Report drawing on research in schools in Scotland and across the UK

-

EdPsy.org.uk – blog on the role Educational Psychologists can play in supervision

Web resources

- Attachment Aware Schools - information

- Education Support

- Education Support - Circle Of Control, Influence And Concern

- Education Support – Mediation

- Debriefing advice

- Give Us A Shout

- Harvard Health article on Stress response

- HeadFit - aimed at the military but trying to appeal to others too

- HSE Stress at work what are the standards 2021

- March on Stress TRiM

- Mental Health First Aid

- MindEd Mindfulness e-learning session

- Trauma informed schools - information

- What Works Wellbeing

Other support groups and caring organisations you may find helpful include:

- The Samaritans – offers a 24- hour helpline for those in crisis. Tel: 116 123

- Cruse – Bereavement Care – Offers counselling, advice and support throughout the UK. Tel: 0808 808 1677

- Assist Trauma Care – Offers telephone counselling and support to individuals and families in the aftermath of trauma. Tel: 01788 551919.

- Drinkaware – offers facts, advice and support to manage drinking. Tel: 020 7766 9900

- Relate – offers relationship support for couples and families. Tel: 0300 0030396

- Stonewall – offers information, advice and support for gay, lesbian, bi, and trans communities. Tel: FREEPHONE 0800 0502020.

- Domestic Violence Intervention Project – offers advice and support to individuals and families who have experienced domestic violence as well as to individuals who want to change their behaviour. Tel: 020 7633 9181.

- Assist Trauma Care - provides information and help for people with PTSD and anyone supporting them

References

- Drury, J, Carter, H, Cocking, C, Ntontis, E, Tekin Guven, S, Amlôt, R. (2019) Facilitating Collective Psychosocial Resilience in the Public in Emergencies: Twelve Recommendations Based on the Social Identity Approach. Frontiers in Public Health. 7, p.141

- Education Support Partnership (2021), Teacher Wellbeing Index, educationsupport.org.uk/resources/for-organisations/research/teacher-wellbeing-index/

- Jones, N, Fear N.T., Wessely, S., Thandi, G. and Greenberg, N. (2017) Forward psychiatry – early intervention for mental health problems among UK armed forces in Afghanistan European Psychiatry 39, 66-72

- Milligan-Saville JS, Tan L, Gayed A, Barnes C, Dobson M, Bryant RA, Christensen H, Mykletun A, Harvey SB. Workplace mental health training for managers and its effect on sick leave in employees: a cluster randomised control trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2017; 4: 850-85

- Solomon Z, Mikulincer M. Trajectories of PTSD : A 20-year longitudinal study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2003 ; 1 63 : 659–666

- Stevenson D, Farmer P. Thriving at Work: The Stevenson/ Farmer Review of Mental Health and Employers. Department for Work and Pensions and Department of Health and Social Care; 2017

The content for these tips was written and edited by Dr Raphael Kelvin and Dr Julie Greer. They draw upon the suite of tips on the MindEd Hub and input from our reference groups of healthcare and education setting experts, to whom we are most grateful.

Education reference group:

John Dexter, John Ivens, Margaret Mulholland, Steve Rippin, Jason Turner

Wider stakeholder group:

Joanna Holmes, Lisa Shostack, Mina Fazel, Sinead Mc Brearty, Andy Bell, Ray McMorrow, Faye McGuinness, Sarah Hannifan, James Brown, DFE (Emma Woodshaw), Sarah Lyons, Steve Cooper

Disclaimer

MindEd is created by a group of organisations and is funded by Health Education England, the Department of Health and Social Care and the Department for Education.

elfh is a Health Education England Programme in partnership with the NHS and Professional Bodies.

© 2022 Education Support Limited, MindEd / Royal College of Psychiatrists and Health Education

Don’t wait for a crisis to call.

We’ll offer you immediate, emotional support.

08000 562 561

Sign up to our newsletter for the latest mental heath and wellbeing resources, news and events straight to your inbox.